The idea behind distributions was born in 2004.

Howard Dean, then a candidate in the United States presidential primaries, used the Internet for a groundbreaking campaign. A volunteer project called DeanSpace, which operated with little involvement or support from the Dean campaign organization, used Open Source as a tool for building community among Dean supporters. Dean's success in achieving front-runner status in the campaign was credited to their use of Open Source, social media, and community.

One of the instigators of the project, Zack Rosen, dropped out of college so he could work to get Howard Dean nominated. Zack’s original idea was to create and distribute a set of tools — including blogs, forums, and calendars — which fellow-advocates all across the country could use to set up local Dean support communities. Other volunteers — like Kieran Lal, who gave up his job at IBM to help — joined the effort. Ultimately these activists deployed over 100 sites using the DeanSpace platform.

And at the heart of the DeanSpace platform, created by the DeanSpace team, was a customized version of Drupal.

Although Howard Dean withdrew from the campaign after a poor showing in the Wisconsin primary, activists like Zack and Kieran forever changed the way political candidates would use the Internet.

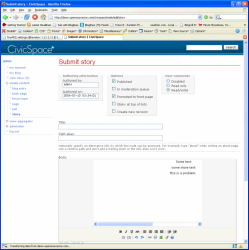

Yet despite Dean’s withdrawal, the DeanSpace team knew they were onto something and continued to work on the platform. They wanted to extend what they had learned and build the tools for a new generation of democracy and advocacy. DeanSpace was renamed CivicSpace, and CivicSpace became the first real Drupal distribution; a distribution for online campaign management and grassroots activism.

Yet despite Dean’s withdrawal, the DeanSpace team knew they were onto something and continued to work on the platform. They wanted to extend what they had learned and build the tools for a new generation of democracy and advocacy. DeanSpace was renamed CivicSpace, and CivicSpace became the first real Drupal distribution; a distribution for online campaign management and grassroots activism.

In 2005, CivicSpace was used to help promote Firefox 1.0 as an alternative to Internet Explorer, the most popular web browser at the time. Using the CivicSpace platform, the Mozilla Foundation built a website called “Spread Firefox.” It activated and enabled the Mozilla community to spread the word and the love about Firefox, either by participating in a project or campaign, or by placing an affiliate advertisement on their website. The goal: trying to replace Internet Explorer with an Open Source solution. One of the highlights of Spread Firefox was a campaign that raised enough money to buy a two-page ad in the New York Times. The ad featured the names of the thousands of people worldwide who contributed to the Mozilla Foundation's fundraising campaign to support the launch of the Firefox 1.0 web browser. The design and development of the New York Times ad was led by Chris Messina, a designer and a volunteer leader at both Drupal and Spread Firefox. So, in a significant way, Drupal helped drive the adoption of Firefox.

CivicSpace was quick to realize that the success of the its distribution depended on the success of Drupal core, and vice versa; so it was agreed that CivicSpace shouldn't “fork” core development — i.e., take the code and modify it separately from the larger Drupal community. As a result, CivicSpace consented to do all its development on the Drupal.org infrastructure: to synchronize releases, submit all patches upstream, centralize bug reports, and share documentation where possible. Thus, with the help of CivicSpace and others, the release of Drupal 5.0 added support for Drupal distributions.

Each distribution takes some set of Drupal modules and themes, and packages them together with the Drupal core, along with custom installation steps, documentation, and so on.

The vision behind distributions was, and still is: to encourage the creation of ready-made, downloadable packages with their own focus and vision, so that folks can hit the ground running, with tools that meet their needs; and to help with adoption and usability. The number of unique distributions Drupal can build is nearly unlimited. They enable Drupal to reach out to both new and different markets. In my mind, the need for distributions has only grown more important over time. If we want Drupal to be relevant long-term, we have to successfully compete with turnkey solutions.

Over the years, we’ve made incremental improvements to how Drupal supports distributions. It wasn't until Drupal 6 — after distribution packaging tools were provided on Drupal.org — that we saw a number of great Drupal distributions emerge: OpenAtrium (an intranet distribution); Acquia Drupal (a convenience distribution for site builders); OpenPublish (a distribution for online publishers); Pressflow (a distribution with performance and scalability improvements); and many many more.

Over the years, we’ve made incremental improvements to how Drupal supports distributions. It wasn't until Drupal 6 — after distribution packaging tools were provided on Drupal.org — that we saw a number of great Drupal distributions emerge: OpenAtrium (an intranet distribution); Acquia Drupal (a convenience distribution for site builders); OpenPublish (a distribution for online publishers); Pressflow (a distribution with performance and scalability improvements); and many many more.

With the release of Drupal 7, we made it even easier to build distributions and to host them on Drupal.org. We brought installation profiles (the kernel of code that assembles a distribution) more inline with modules, in terms of their developer API — which has significantly helped reduce the learning curve associated with building distributions. Additionally, Drupal.org’s distribution packaging tools can now assemble and package external code libraries within distributions, such as WYSIWYG editors, media players, and image galleries. And now, with the development of Drupal 8, we are working on eliminating more pain-points around the packaging, distribution, and deployment of Drupal distributions by further de-coupling the underlying parts of Drupal core to allow for more fine-tuned customization by distribution authors.

Today, there exist more distributions of Drupal than ever before, as well as more targeted and easy-to-use distributions. For example, Commerce Kickstart provides a highly polished out-of-the-box solution for creating online storefronts; Commons provides powerful social features out of the box, such as groups and activity streams; Spark is used to prototype and build cutting-edge, authoring, experience improvements in Drupal 7, such as mobile-friendly navigation, built-in WYSIWYG, and inline editing. These improvements are scheduled for inclusion in Drupal 8 core.

Drupal is the only Open Source content management system that actively encourages its community to build and share distributions. While we in the Drupal community continue to progress in making distributions easier to build from a technical point of view, we have yet to figure out a business model. Building and maintaining a high-quality Drupal distribution is no small task. We need to figure out how to make it “commercially interesting” (or, at a minimum, “commercially viable”) for organizations to invest the time and money it takes to build and maintain great distributions. I hope to see many entrepreneurs and organizations experiment with potential business models. It is an exciting challenge; we are charting unknown territory. But if we crack the code, distributions will be a huge game changer for Drupal.