Recently I found myself musing about two Drupal-related posts from back in 2007 that projected very different futures for the software project.

Recently I found myself musing about two Drupal-related posts from back in 2007 that projected very different futures for the software project.

The first was by Jeff Robbins of Lullabot: “How Drupal Will Save the World.”

Robbins took as his reference case a community in Nigeria facing exploitation by a multinational oil company. Drupal, he suggested, could empower the community and “give a voice to those who might not otherwise be heard,” driving an internet that was “a powerful force for social change.” To achieve that vision, Robbins laid out technical challenges, centered on making the software easier to learn and use.[1]

A few months after Robbins’ post, Drupal contributor Fergus Geraghty initiated a Drupal.org discussion, “7 million reasons to consider democratising Drupal?” Drupal project lead Dries Buytaert had recently co-founded the company Acquia, and Buytaert’s start-up had just announced its first round of $7 million in venture capital financing. Geraghty expressed concern that the new commercial demands of Acquia could come to shape the overall direction of Drupal, pushing the project in the direction of profit maximization. Against this future, Geraghty proposed the creation of a co-operative to serve as the owner of the Drupal project.[2]

Seven years later, which of these futures are we living? Is Drupal empowering the marginalized and saving the world?

Or is it serving “the man”?

Software Freedom and Social Change

The idea that Drupal and free software could have a role in revolutionizing society might not be as off-the-wall as it sounds.

In Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, the 19th century anarchist Peter Kropotkin countered the social Darwinist “survival of the fittest” thesis by arguing that cooperation was a driving force of evolution and a basis for free human societies.[3]

Late in his life, Karl Marx mused that the crises of modernity could be overcome only through co-operative production for use rather than profit or "the elimination of capitalist production and the return of modern societies to a higher form of the most archaic type - collective production and appropriation."[4]

Copyleft, “a general method for making a program (or other work) free, and requiring all modified and extended versions of the program to be free as well,”[5] has clear roots in radical political ideals and projects.

Against the dominant capitalist models, free software suggests an economy and society where collaboration rather than competition is the core paradigm and where use value trumps profit maximization. “From each according to ability, to each according to need,” the early utopian activists cried.[6] Free software seems to hold the promise of realizing their progressive vision in the heart of advanced capitalist society.

And Drupal is more than free software – it’s a platform built by and for participation and collaboration. Drupal originated as a student project connecting a group of friends at the University of Antwerp. From its first lines of code, Drupal has connected people and enabled peer-to-peer communication – essential elements of a participatory, democratic society. For many early Drupal adopters and contributors, blending progressive social ideals with free software development seemed a perfect fit.

CivicSpace Labs – one of the first Drupal shops – emerged from an explicitly political context and had empowering social change as its primary focus. Core Drupal systems like the installer and the update system owe their origins to CivicSpace. In a very practical sense, Drupal owes a lot to early adopters motivated by the ideals of free software and social activism.

Taking the Pulse

By many measures, the project of saving the world with Drupal is alive and well.

Participation continues to grow. The number of Drupal contributors has jumped significantly with each major version, a trend that continues with the upcoming Drupal 8 release. Well over a million websites benefit from the free software collaboration that powers Drupal core and its thousands of contributed add-ons.

Positive examples stand out of Drupal engagement on critical social fronts including gender and LGBT issues. Drupal contributor Angie Byron has been a prominent advocate for – and inspiration to – women in technology. In 2010, Byron proposed updating Drupal community practice on gender, enabling a more inclusive, non-binary gender designation on Drupal.org. While the initiative met with significant resistance, ultimately the proposed change was adopted.[7]

Drupal is powering websites across the spectrum of social change organizations and movements. At Drupal shops like Koumbit and Palante Technology Cooperative, social justice is an explicit commitment reflected in democratic and co-operative organizational structures.

But for anyone dreaming of Drutopia, there’s no shortage of warning signs. One of the biggest came in late 2009 with the announcement that whitehouse.gov had relaunched on Drupal. The software that once ran tiny alternative sites now was powering the public face of the leading capitalist power. Progress?

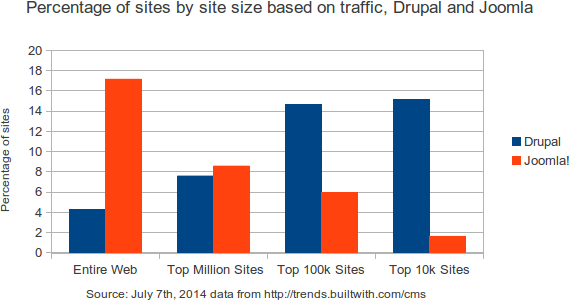

Figure 1: Drupal and Joomla Usage by Site Size

One way to get a handle on who Drupal is serving is to look at usage statistics. The data provided by builtwith.com provide an incomplete but potentially useful benchmark.[8] Figure 1 shows July, 2014 usage data for four data categories based on the level of site traffic: the entire internet, the top one million sites, the top 100,000 sites, and the top 10,000 sites. The data represents percentages of all known sites. As well as Drupal data, the chart includes data for Joomla!, a free software CMS that perhaps most closely parallels Drupal. Like Drupal, Joomla! powers a significant percentage of the Internet, is written in PHP, has a global team of contributors, and is licensed under the General Public License (GPL).

The data for Drupal shows a clear trend: as site size increases, so does the level of Drupal usage, from 4.3% of the entire web to 15.2% of the top 10,000 sites. Notably, when going from the top million to the top 100,000 sites, Drupal usage numbers nearly double from 7.6% to 14.7%.

In contrast, Joomla! data have the opposite structure. While 17.1% of the entire web shows up as Joomla!, the number for the top 10,000 sites is only 1.6%.

In both absolute and comparative terms, Drupal appears to be highly focused in the highest-traffic, top-end sites.

And if Drupal already is oriented towards high-end users, signs are that this trend will only increase. Some commentators have observed that – even more than with previous versions – changes in the forthcoming Drupal 8 version stand to disproportionately benefit high-end, high-traffic sites, while potentially leaving smaller Drupal sites behind (see “Small Sites, Big Drupal”).

In a 2013 blog post, Drupal contributor Larry Garfield wrote that Drupal followed what he described as a normal project trajectory in which “larger and larger sites tend to be more and more profitable and more and more interesting. Small sites become a ‘solved problem,’ and moving up market is the natural movement.”[9]

But the contrasting data from Joomla! strongly suggest there’s more to the story.

Structured for Profit?

When Geraghty raised the possibility that Drupal could become increasingly enmeshed with corporate interests, he focused squarely on the centralized power structure of the project. Reaction was swift and sharp. One commenter described Gerathty’s post as “Slippery, innuendo-laden suggestions about what Dries, Acquia, and its investors might be doing or might do in the future.”[10] Within days, the post was locked down to prevent further comments.

But for purposes of our comparison of futures, it’s worth giving Gerathty’s points a second look. How is Drupal decision-making power invested?

Drupal is structured on a model often called, by its proponents, “benevolent dictatorship for life” (BDFL). Under this model, a single founder – in Drupal’s case, Dries Buytaert – exerts final control.

Today, several bodies, theoretically, exert influence or control over the Drupal project.

- Core committers These are the individuals who have final say over which particular changes are made to Drupal core. There is a single permanent core committer, Buytaert. For each major version of Drupal, Buytaert appoints one or more “branch maintainers” who commit changes to that version of the software.[11]

- Official Drupal 8 initiative leads Drupal 8 development was organized around a series of official initiatives, approved by Buytaert, who appointed an individual to lead each initiative.[12] Official initiatives shaped the core directions and solutions adopted in Drupal 8.

- The Drupal Association The Drupal Association is a nonprofit that, according to its mission, “fosters and supports the Drupal software project, the community and its growth.”[13]

- Drupal Working Groups Three Working Groups – Community, Documentation, and Technical – oversee key areas of the Drupal project. Individuals are appointed to these groups by Buytaert or his designate(s).[14]

Beyond formal decision-making roles, the individuals whose code contributions are accepted also exert a significant influence on the software and, by extension, the Drupal project.

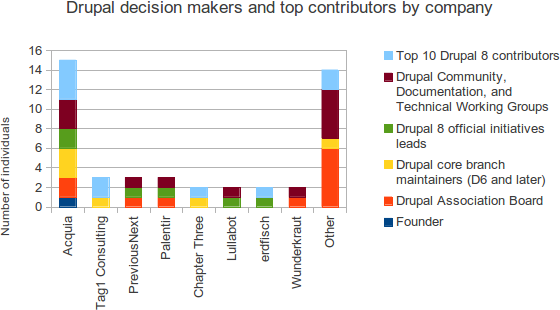

Figure 2: Drupal decision makers and top contributors by company

Figure 2 draws on Drupal.org data to trace the relationship of Drupal project decision makers to the current companies they list on their Drupal.org profiles as of July, 2014. (Users of Drupal.org can identify a “Current company or organization” on their user profiles.) Top contributor data is from DrupalCores.[15] Particular individuals may fill multiple roles and therefore be counted more than once. Companies listed are those that fill two or more places. Members of these groups serve as individuals rather than formal representatives of their associated companies.

One clear trend in the data is that in all six groups, Acquia has a higher number of places than any other company. At fifteen total places, Acquia preponderates with five times the number of the next closest companies.

Of the eight companies listed, four have from twenty to fifty employees or contractors listed on Drupal.org, one has over one hundred, and one – Acquia – has over three hundred. It seems fair to say that the companies most represented in Drupal structures are medium- or large-sized Drupal companies.

Acquia has a partner program in which companies receive client referrals from Acquia and in return remit a percentage of revenues to Acquia. Of the seven non-Acquia companies listed in Figure 2, five are Acquia partners.

When it restructured in 2011, relocating from Belgium to the U.S., the Drupal Association produced guidelines for board composition, which should reflect “the various perspectives of the members of our community (volunteers, small shops, large shops, large integrators, in-house teams, designers, end-users, etc).”[16] Today, three board members are from Acquia partner companies, all companies in Acquia’s “Enterprise Select” category, and of the remaining Drupal-based regular board members, one is the CEO of a company listed on Drupal.org with usual project budgets up to €2 million; one is on staff at PayPal; and the two most recent board appointments, in May, 2014, were for senior staff at Pfizer and NBCUniversal.

In short, the board is increasingly enterprise-oriented.

None of this data indicates a conspiracy on Acquia’s or any one else’s part to stack Drupal decision making with their people. Any company amassing top Drupal talent by the dozens, through hiring and/or acquisitions, could be expected to end up with influential Drupal participants.

However, the data does suggest that a trend towards enterprise interests in the software is closely coupled with the power structure of the Drupal project, centred on Buytaert as founder of Drupal and Acquia. If this isn’t the future Geraghty was concerned about, it sure bears a striking resemblance.

Lessons

In retrospect, for all its appealing idealism, Robbins’ 2007 post seems remarkably naive in its program. The basic premise – that software developers, mainly in the U.S. and Europe, will be the ones to empower African villagers – seems paternalistic. Critically, his recipe for saving the world is entirely technical. No attention is given to the social structures or power dynamics that would be involved in enabling marginalized or exploited classes effectively to challenge corporate or state power.

While on some fronts it continues (in Robbins’ words) to “give a voice to those who might not otherwise be heard,” Drupal increasingly is reinforcing the power of those who already have the loudest voices and the deepest pockets. Returning to his reference case of a Nigerian community facing down an oil multinational, it’s hard not to conclude that, of the two, it’s the oil company that’s more likely today to have Drupal in its corner.

The experience of Drupal raises important questions for both free software and politically progressive projects.

- The cult of growth Self described “evangelists” of Drupal – and free software in general – often have uncritically promoted growth as a good in and of itself. Hence, for example, the growth-oriented mission of the Drupal Association quoted above. We could use a much more nuanced discussion about growth and its attendant risks – and differential benefits.

- White guys to the rescue The idea that a group of predominantly male, predominantly European or Euro-American geeks is going to “save the world” through brain power might fit a Hollywood plot line, but calls for a healthy dose of scepticism when it appears off the screen.

- Critical debate Critical perspectives, even (or especially) ones that challenge accepted truths and power structures, are essential to the health of any project. Rather than shutting down discussion, it’s important to recognize, support, and, where needed, fight for openings for debate and renewal.

- Structure matters At the risk of stating the obvious, proponents of participatory, grassroots social change have reason to be doubtful of projects with a highly centralized, “dictatorship” model.

For all its challenges, the pursuit of progressive political ideals within and through the Drupal project remains alive and active. And the Backdrop fork of Drupal reminds us in the most direct way possible that, while software freedom is not in itself enough, it does make a difference.[17] Whoever may claim the trademark or exert founder’s rights, no one person or company “owns” Drupal. We all do, and our freedom includes the ability to take our collective work in our own direction.

In short, Drupal is perhaps not so different from other sites of social change activism. Emerging alternatives don’t exist on some abstract plane, removed from the dynamics of state power or advanced capitalism. Instead, alternatives are themselves deeply embedded in and shot through with the logics of market society. Yes, those trying to use and shape Drupal for radical social change are working at the margin. But, as feminist theorist bell hooks wrote (in a very different context), the margin can be “the site of radical possibility.”[18]

Personal narratives

Abstract questions of saving the world or working for capital accumulation of course translate into real-lived experience. For me personally, the tensions between free software and working for “the man” are ones I feel every day.

For the past four years, I’ve focused on building and maintaining a Drupal distribution, Open Outreach, aimed at meeting the needs of small community and activist groups. With my spouse, Rosemary Mann, we’ve built the distribution almost entirely as a volunteer project. Today, I’m happy to see Open Outreach powering websites for Cooperation Network for Renewable Energy in Malawi, South Central Indiana Jobs With Justice, and Women Occupy San Diego.

But volunteer development and gratification don’t pay the bills. I also contract part time for Tag1 Consulting, one of the high-end companies listed in Figure 2.

[Editor’s note: This magazine is published by Tag1 Publishing, a subsidiary of Tag1 Consulting.]

I actually love my work at Tag1 – I get to collaborate with and learn from a creative and super-smart team on varied and challenging projects. But it’s not exactly what I expected when, most of eleven years ago, I picked the tiny and at that time obscure Drupal project for the community sites I was building at a small NGO.

Image: "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised"> by **AB** is licensed under CC BY 2.0

________________

[1] Jeff Robbins, “How Drupal Will Save the World,” June 20, 2007, http://wdog.it/4/2/save.

[2] Fergus Geraghty, “7 million reasons to consider democratising Drupal?” December 20, 2007, http://wdog.it/4/2/million. See also Nedjo Rogers, “Making Drupal fully ‘community-driven’: A Proposal for restructuring the Drupal project,” January 20, 2005, http://wdog.it/4/2/struct.

[3] Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor In Evolution, undated [1902]. Boston, Extending Horizons Books.

[4] “K. Marx: Drafts of a Reply”, in T. Shanin (ed.), Late Marx and the Russian Road, 1984. London, Routledge and Kegan, Paul, p. 114.

[5] “What is Copyleft?”, http://wdog.it/4/2/left.

[6] See http://wdog.it/4/2/wiki.

[7] “Expand Options in the Gender Profile Field”, March 24, 2010, http://wdog.it/4/2/gender.

[8] BuiltWith top million site data come from Quantcast and are US-centric. http://wdog.it/4/2/faq. For a detailed presentation on Acquia, Drupal, and the enterprise, see the webinar “Setting the Record Straight: Drupal as an Enterprise Web Content Management System,” by Dries Buytaert, May 19, 2014, http://wdog.it/4/2/web.

[9] Larry Garfield, “Dropping Forward,” Oct. 17, 2013, http://wdog.it/4/2/drop.

[10] http://wdog.it/4/2/million.

[11] See “Core Developers,” http://wdog.it/4/2/core.

[12] “Drupal 8 Official Initiatives,” http://wdog.it/4/2/init.

[13] “About the Drupal Association,” http://wdog.it/4/2/da.

[14] “Governance,” http://wdog.it/4/2/gov and sub-pages.

[15] DrupalCores lists Drupal 8 contributors based on analysis of commit messages. http://wdog.it/4/2/dc.

[16] “Recommendation for a New Governance Model,” downloadable at “Renewing the Organizational Structure of the Drupal Association,” July 11, 2011, http://wdog.it/4/2/renew.

[17] See http://wdog.it/4/2/bd. See also this discussion of decision making structure in Backdrop: http://wdog.it/4/2/bdstruct.

[18] bell hooks, “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness,” Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, 1990, Boston, South End Press, p. 209.

Comments

Do you have the data source for your chart of top decision-makers? Because, at first glance, it appears to be quite misleading.

1. First and foremost, it's very imbalanced to only represent folks' current employers. tim.plunkett and I worked on the Views in Core initiative, and are both in the top 10 patch contributors to Drupal 8. Except... Views in Core was done before either of us started at Acquia, and most of our other contributions were made before we started at Acquia as well. Compare:

git log --before=2014-06-01 --after=2011-03-09 | grep "tim\.plunkett" | wc -l

985

git log --after=2014-06-01 | grep "tim\.plunkett" | wc -l

180

So not only is the chart overstating Acquia's influence by crediting them with our previous contributions, it's also under-crediting Tim's previous employers, Zivtech and Stanford, as well as the hundreds of community contributors who gave money to the chipin that paid my salary in 2012 as I worked on Views in Core. (Also see the paragraph about this at http://chapterthree.com/blog/drupal-8-and-the-enterprise.) Similarly, EclipseGc only recently joined Acquia, and his work on the Blocks and Layouts initiative was concluded long before that.

2. I definitely believe that we should always be mindful of conflict of interest, but crediting a company with work that's done by a volunteer that happens to work for them is unfortunate. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2288727 for work that's being done on Drupal.org to help contributors distinguish between work sponsored by their companies or clients, and work they are contributing on their own.

3. It is statistically unsound to represent the top 10 patch contributors, but exclude the work of over 2500 other contributors to D8 core, most of whom would fall under your "other" category. By not counting these contributions in your graph, you're disregarding more than 75% of the work that has been done on Drupal 8 core.

4. It also looks like you might be double-counting people? Not sure on this because I don't know what data are represented, but Gábor for example is both an official initiative lead and a top 10 contributor. It would be misleading to represent that as if there's a patch-contributor Gábor who's different from an initiative lead-Gábor; so many of his patch contributions support his work on the initiative he led. Similarly, webchick-the-core-committer is the same webchick as the one who sits on the Community Working Group. Overall, the Acquia column seems a lot bigger than the list of people in Acquia that fit there, so that also makes me wonder about the rest of the chart.

So between when I posted the above and when it was published, I wrote a whole post: http://xjmdrupal.org/blog/contribution-influence-drupal-8 :)

Thanks for posting these questions. I didn't see this comment until now so I'll respond here, though I realize your related blog post includes additional information.

I wrestled with this question when putting together the data. The chart tries to provide a overview by bringing together what are in effect disparate data sources. Indeed, individuals change employers over time, and it's not necessarily self-evident what point or period in time is the most relevant for a given parameter, for example, Drupal Association board membership. For the sake of consistency, I opted to use a snapshot in time. However, I'm interested to hear other perspectives and alternate data lenses.

It's important to note that there's not necessarily linear cause-effect relationship in the (indirect) association of leaders with companies. It's relevant to look at how working for a given company might contribute to attaining a leadership role, for example, through employer sponsorship of work. It's also relevant to look at the opposite relationship: how attaining a leadership role might contribute to gaining employment in certain companies. Though they are distinct, both of these questions or relationships shed light on the research question: the structure of decision-making power.

Agreed. I recently raised a similar issue related to the handling of SA-CORE-2014-005, the so-called "Drupalgeddon" bug. Assigning credit is not my interest here. Rather, as I noted, the interest is in how decision-making power is invested, and specifically to trace associations with corporate bodies. Because Drupal is a community project, such associations are necessarily indirect. As I noted in the article, "Members of these groups serve as individuals rather than formal representatives of their associated companies."

The aim here is to meainingfully incorporate Drupal 8 contribution data with the other parameters, using the same metric of one unit per individual. In doing so, I arbitrarily chose a cutoff of 10. I did so because a much larger number, while more inclusive of contributors, would have skewed results by weighting this parameter excessively in relation to others in the chart.

That said, contribution data certainly is worth a separate, more detailed, and more inclusive analysis.

I realize it's potentially confusing to count individuals in each of their multiple roles. I tried to clarify this in the text of the article, but could have taken more care, especially since readers may interpret a graphic without wading through the print. It would probably have been clearer and more accurate to label the chart's Y axis "Number of positions" or "Number of roles" rather than "Number of indviduals".

Counting one unit of influence per position or role filled, however, is definitely by design. The decision-making responsibility of, for example, a Drupal Association board member is very distinct from that of, for example, a Drupal 8 initiative lead. Since we're assessing decision-making power, not numbers of individuals involved in Drupal, we count once per position filled.

By way of comparison, say we were studying the influence of a particular family on corporate governance. As a measure, we might count the number of boards positions held by members of that family. Yes, one family member might be on the boards of multiple corporations. However, we're counting board positions, not family members, so we count once per board position.

Yes, I have a spreadsheet. I can't attach it to a comment, but I'll look into where I might post it.

You wrote: "It's important to note that there's not necessarily linear cause-effect relationship in the (indirect) association of leaders with companies. It's relevant to look at how working for a given company might contribute to attaining a leadership role, for example, through employer sponsorship of work. It's also relevant to look at the opposite relationship: how attaining a leadership role might contribute to gaining employment in certain companies. Though they are distinct, both of these questions or relationships shed light on the research question: the structure of decision-making power."

I definitely agree this is an important question and worth exploring more. As you mention in your post, companies that hire a lot of Drupal talent end up hiring prominent contributors almost as a matter of course. With the examples of tim.plunkett and myself, we both were able to get our current jobs *because* of our independent contributions. Contribution and community reputation then affect some companies' hiring decisions, which in turn introduces all the risks from resource inequality described in http://www.ashedryden.com/blog/the-ethics-of-unpaid-labor-and-the-oss-co...

I also think it's valuable to look at it from the other side, that is, who *contributors choose* to work for. Over the past two years, numerous active community members have gone to work for Tag1, PreviousNext, Lullabot, etc. What is it about those companies that make them desirable to people who have both the interest and resources to already be active in the community? Things like vacation policy, employee protections, allowing remote work, supporting contribution, etc. all come to mind as potential factors. Are there takeaways for other companies? For contributors who choose to remain independent? For people who facilitate volunteer contribution?

You lost me when you say that one of the first warning signs was whitehouse.gov adopting Drupal in 2009. Noam Chomsky would agree with you but I don't. This is a strong article in many ways, and you raise necessary questions. But what would have been very helpful is a clearer idea of what enterprise-level development means and how it changes the larger goals that most of us in the Drupal community have for social change. I would go toe-to-toe with Noam Chomsky with my ambitions for using Drupal to change the world, and for me the limitations have been at the interface level, not with getting sites set up but with getting users comfortable with using it, and I am frankly astonished at the improvements that come with Drupal 8. We're in this for the long haul. After Drupal 8 will come Drupal 9 and Drupal will continue to evolve. The strength of Drupal lies entirely with its community, and the challenges of agreement and cooperation are as fundamental to our strength as good code. Noam Chomsky's principal scientific ideas regarding language development have been found to be wrong in recent years, and I believe his level of political dissent will follow the same path. Uncritical acceptance does no one any good, but neither does a generalized dissent.

@Ed Carlevale: thanks for your lively comment!

I covered some of this in my article "Small Sites, Big Drupal", in the print ediiton of this issue, but it's not yet published on this site.

Recently I've been digging into the work for preparing distributions support in Drupal 8, including writing what may become the basis for a Drupal 7 Features module. As part of that work I came across what I think is still a little understood implication of the configuration management system in Drupal, and both blogged about it and began work on a module to help address the issue. In brief, the focus on staging configuration - a use case that heretofore at least has mainly been a concern of larger sites - presents particular issues for smaller sites and distributions. An example, it seems to me,, of how focusing on one use case can inadvertently create barriers for others. We can try to address the issue in contrib, but doing so will reach a small number of sites. We could fairly easily fix the problem in Drupal 8.1 or a subsequent release--given the political will.

See also Alex Pott's followup blog post.